We Get the Schools We Pay For

Three ways to boost quality and equality in America’s K-12 schools

Two weeks ago, I wrote about five hard truths Democrats must face on education. When I was thinking about three of them—the national teacher shortage, declining student learning, and growing inequality—I was really thinking about Jamarria Hall.

In 2016, 16 year-old Jamarria was growing up on the west side of Detroit, riding the bus 26 miles a day to attend a public school on the other side of town. Despite the lengths he went to get to school, policymakers did little to make it worth his while. The facilities were unsanitary and often unsafe. There was a shortage of textbooks and certified teachers. And there was no support for English learners.

Jamarria knew he deserved better, and he went to bat for himself and his classmates. In Gary B. v. Whitmer, Jamarria (using a pseudonym as a minor) sued Governor Gretchen Whitmer to force the state to provide better and more equal education for Detroit students like him. He was wading into a longstanding debate in our country about what the 14th Amendment actually means when it requires governments to provide “equal protection of the laws.” But more importantly, there was a common sense argument he was making: If he couldn’t learn to read or write because his schools were so poor, how could he exercise his other constitutional rights or participate equally in society?

In 2020, a federal district court ruled in his favor, recognizing a “fundamental right to a basic minimum education” for the first time in U.S. history. Governor Whitmer also agreed in an initial settlement to request nearly $100 million in new funding to improve school facilities and literacy education in Detroit. But these victories were short-lived. A few weeks later, an appellate court overturned the ruling. To make matters worse, Whitmer’s spending proposal stalled for years in the Republican-run state legislature, all while COVID accelerated a long decline in reading scores in Detroit.

At just 16, Jamarria recognized a simple truth that still evades too many of us. Students are failing to learn, teachers are leaving, and our schools are growing more unequal because the financing of our K-12 education is broken. It’s a system of haves and have-nots that not only leaves students like Jamarria worse off, but it also holds back our communities and our economy.

We don’t need to remake the whole system of school funding from scratch; that would be unpopular and is probably impossible. But the federal government can build on past successes to make school funding more fair and fix one of the most glaring problems facing our schools.

It’s not that complicated: School funding matters

One of the obvious problems is also one of the central ones: We aren’t spending enough nor spending wisely. We already know that even modest increases in school funding can make a huge difference for students. When California increased statewide K-12 education spending from $15,080 per student in 2013 to $17,260 per student in 2019, each $1,000 (6.6%) increase in per-pupil spending sustained for just 3 years increased students’ math and reading scores by an entire grade level and raised students’ high school graduation rate by 8.2 percentage points (for comparison, the statewide high school graduation rate in California in 2013 was 79%). Similarly, a $1,000 per-pupil spending increase in Texas led to lower dropout rates and higher reading and math scores.1

Students also benefit from increased school spending long after they graduate. A 10% increase in per-pupil funding that is maintained for all 12 years of a child’s education after kindergarten boosts future wages by 7.25%, reduces their adult poverty rate by 3.67 percentage points, and improves college enrollment and completion. Kids from low-income families consistently benefit the most from school funding increases. We also know that when schools get more funding, they most often use it to reduce class sizes, increase teacher salaries, lengthen the school year, and improve school facilities, all needed steps to improve educational outcomes for students.

This is not to say we can just throw money at our schools and expect all of the problems to be solved—if only education policy were that easy! But we do know that school financing is a crucial issue because so many students and schools today lack the basic, foundational resources they need.

Students and schools most in need get the least

Per-pupil spending in American schools varies dramatically across schools. This is largely because schools are primarily funded through local property taxes, with wealthier communities generally more able to raise their own taxes in order to better fund their schools. Out of every dollar spent on K-12 schools in the U.S., 44 cents comes from local property taxes and 45 cents from state school aid, while only about a dime comes from the federal government.2

Take my home state of Wisconsin as an example. I teach in Oregon School District, a suburban and rural school district in southern Wisconsin that spends about $17,000 per student each school year. However, like many relatively affluent communities, Oregon has consistently voted to increase local school funding, so most of our funding comes from local property taxes, not state or federal school aid. As a result, our high school is newly renovated and our district offers good pay, solid benefits, and exceptional support for new teachers. Our high schoolers score in the 88th percentile across all subjects on the statewide Forward exam, and we’re steadily closing our achievement gap between low-income and higher-income students. Sure, there are problems like at any school, but overall it’s a great place to teach and learn.

Drive a couple hours east, and you’ll find yourself in Milwaukee, where the public schools spend about $18,800 per student. (That might sound better than Oregon, but remember that Milwaukee has a student population that is about 6 times more diverse, 6 times poorer, and 4-5 times less likely to be reading or doing math at grade level than Oregon’s.) Then consider that if you drive 20 minutes north to suburban Nicolet Union High School District (NUHSD), a suburban district which spends $26,300 per student to educate a significantly wealthier, whiter student population than Milwaukee. The difference? NUHSD raises over $17,000 per student from local property taxes, while Milwaukee Public Schools raises less than $5,000 per student from local taxpayers.

School funding inequity is a problem in rural areas, too. On the opposite side of Wisconsin you’ll find the small town of Menomonie, where the local schools can only spend $14,600 per student to serve a high-poverty rural community that is home to many Hmong American refugees and their descendants. Like Milwaukee, Menomonie can only afford to raise a small fraction of their funding from local property taxes. Relying so heavily on local property taxes to fund our schools clearly increases racial inequality—school districts educating the most students of color receive $2,700 (16%) less state and local funding per student than the least diverse school districts.

There’s precedent for using federal funding to fill the gaps

Photo from EducationWeek, Franke Wolfe, and The LBJ Library

When President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) into law in 1965, he nearly tripled federal funding for K-12 schools. The federal government successfully used the “carrot” of ESEA funds to compel Southern states to comply with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and desegregate their public schools.

Today, 45 cents of every dollar spent on K-12 schools in the U.S. comes from state governments, but only 8 states provide at least 20% more state aid to high-poverty school districts (where at least 30% of students qualify for free or reduced price school lunch) than more affluent districts, while 15 states actually provide less funding to high-poverty districts. Democrats should pledge to take action to correct this injustice.

Here’s how it would work. Congress would propose a significant increase in federal school aid for states that provide at least 20% more per-pupil state aid to schools in high-poverty school districts. States would use this new federal funding to cover the cost of increasing aid to high-poverty school districts (in the interest of fairness, the handful of states already meeting this 20% threshold could receive some amount of funding as well). As with Medicaid expansion, the federal government could pay 100% of the cost of equalizing state school aid for the first three years, and then gradually reduce the federal share of this cost in each subsequent year. The federal share of the cost of school funding equalization would eventually settle at a predetermined threshold, with higher levels of permanent federal aid for states with lower capacity to raise new revenue, such as Mississippi or Iowa. This is similar to how Medicaid funding works; the federal government covers between 50% and 77% of the cost of each state’s Medicaid program and 90% of the cost of Medicaid expansion. Following this model, a relatively small, partially temporary increase in federal funding could bring about a much larger long-term realignment in state school aid.

This policy would not dramatically alter the balance of power between the federal government, the states, and local school districts. It leaves states and high-poverty local schools with a lot of flexibility regarding how these new federal funds will be spent. And it is not fundamentally different from past instances of Congress leveraging federal funds to compel states to raise the drinking age to 21 in the 1980s or desegregate schools in the 1960s.

The cost of this school funding equalization initiative is difficult to estimate, but let’s be very conservative and assume that school funding equalization would require the federal government to foot the bill for a 20% increase in state school aid across all fifty states and D.C. That would cost the federal government $77 billion annually in years 1-3, and less in each subsequent year as states gradually picked up more of the tab. That’s a lot of money (current federal K-12 school aid totals $119 billion per year), but we can afford it. The Trump tax cuts for the rich cost over $400 billion per year, and before all the DOGE craziness, implementing common-sense GAO efficiency recommendations saved the federal government $67.5 billion in 2024 and $100 billion from 2021-23. Greater education funding will also likely pay for itself over time by generating (taxable) economic growth, helping students earn higher (taxable) incomes.

Would every state take the new federal money? As evidenced by Republican-led states’ reactions to the 2009 stimulus act and Medicaid expansion, definitely not. Oh well! And as of 2025, only 10 states have still not expanded Medicaid. There is broad, bipartisan public support for increasing school funding and promoting educational equality, and among the 8 states that currently spend at least 20% more on students attending high-poverty schools, 3 are reliably Republican and 5 are solidly Democratic.

Here’s where new school funding should go

More dollars will only help students if they are spent well. In addition to the school equalization program described above, there are two areas where I think additional federal, state, and local education funding could be spent most effectively: boosting pay and support for new teachers, and following the “Mississippi Model” for providing a good literacy education to every child.

Recruit and retain more great teachers with higher pay and support.

Chart from Economic Policy Institute

First, to address the national teacher shortage, policymakers should increase teacher pay and provide additional support for new teachers. One in three new teachers are currently leaving the profession within 5 years, and 78% of all teachers have considered quitting in the past 5 years. Low teacher pay, while not the whole story, is certainly a big part of the problem: “Inadequate pay and benefits” is the most common reason teachers cite for quitting. As one teacher said in a 2019 poll, “I work 55 hours a week, have 12 years’ experience, and make $43,000. I worry and stress daily about my classroom prep work and kids. I am a fool to do this job.” Adjusting for inflation, the national average starting salary for a teacher has declined from $56,929 in 2011 to just $46,526 in 2025. Even after accounting for better benefits, teachers earn 14% less than other college graduates.

Low teacher pay also drives good teachers to wealthier, whiter school districts. For instance, voters in my suburban school district recently passed a local property tax referendum to fund teacher pay raises; first-year teachers in my district now earn about 13% more than the national average. Of course, many school districts are not willing or able to raise local property taxes to do this. This is why state and federal governments need to step in.

As a condition of receiving the school aid equalization funding mentioned above, the federal government should require all states to establish a teacher salary floor. At a bare minimum, these statewide teacher salary floors should boost the starting salary for a first-year teacher at every public school in the state to the 2011 inflation-adjusted national average of $57,000 per year (adjusted to the cost of living in each state or school district). Congress and the states should also consider offering incentives to make it more financially feasible for talented, motivated young people to get into teaching in the first place. For instance, Michigan provides $9,600 stipends to student teachers, and state and federal student loan forgiveness programs for teachers serving in high-need districts should be expanded. South Dakota allows school para-professionals to earn a teaching certification while continuing to work full-time with students receiving a special education.

However, raising teacher pay is not a silver bullet to kill the teacher shortage. New teachers also need stronger professional support. During my first two years teaching at Oregon High School, I was required to participate in a “New Educator Program.” I attended monthly professional development sessions with my fellow new educators, and was provided with weekly non-evaluative classroom observations and reflection meetings with an experienced instructional coach. Pay increases, new teacher programs, and instructional coaching are all proven to improve performance and boost retention for new teachers.

The Mississippi Model: Provide every child with a great literacy education.

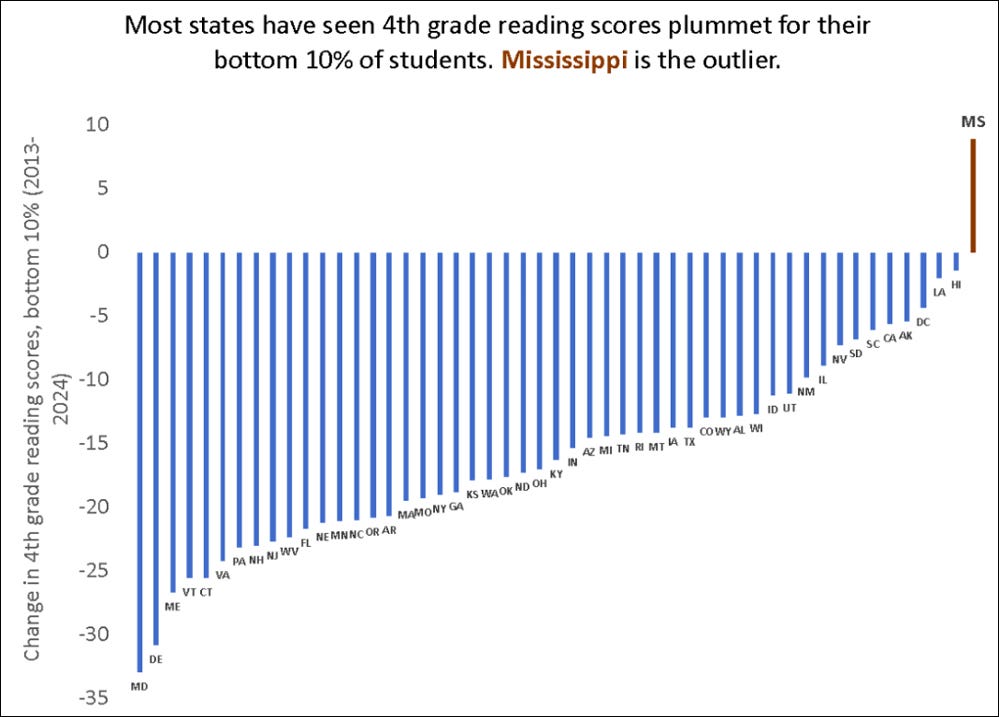

Chart from The 74 Million

Hear me out: Democrats across the country should shamelessly copy Mississippi’s reforms to literacy education. Mississippi is the poorest of the 50 states, and once had some of the lowest-performing K-12 schools. However, in what has become known as the “Mississippi Miracle,” the Magnolia State has quietly built one of the strongest records on K-5 literacy education in the nation. Mississippi now boasts the nation’s top demographic-adjusted reading and math scores, and is the only state where 4th-graders continued to get better at reading during and after the pandemic. Mississippi achieved this by implementing a variety of reforms, most notably:

Providing literacy coaches to help train K-3 teachers and provide intensive literacy instruction to students the poorest elementary schools in the state;

Universal literacy screenings for every student in grades K-3. These screenings were used to identify students who need extra support to read at grade level and create an “Individual Reading Plan” for each of these students. Screening results were also quickly shared with both teachers and parents to allow them to help each student improve their literacy skills.

Early Learning Collaboratives - targeted, state-funded 4 year-old pre-K programs.

3rd-grade students who were still reading well below grade level at the end of the school year were held back or “retained” unless granted a “good cause exemption.” Although retention policies like Mississippi’s are fairly rare and controversial, independent research indicates that this practice alone accounted for 22% of the reading gains in Mississippi since 2013.

These reforms are not free, but they are relatively low-cost. Mississippi spends only $15 million per year on its K-3 literacy program (about $32 per K-3 student) and spent a total of just $70 million from 2013-2022 on its 4 year-old pre-K programs. Similar policies have proven to be effective in other states, and other states have innovated on Mississippi’s model. For instance, Alabama sent over 30,000 3rd-graders at risk of being held back to summer reading camps in 2022, and half were reading at grade level by the end of the summer and were able to progress to the 4th grade on time. Crucially, almost all of these reforms to literacy education could be implemented at the local, state, or federal level right now.

Final Thoughts

Sixty years ago, after signing the ESEA into law outside the one-room Texas schoolhouse that he attended as a child, Lyndon Johnson (a former public school teacher) rightly described the law as “a major new commitment of the federal government to quality and equality in the schooling that we offer our young people.” By making school funding more equal, getting more great teachers into classrooms, and making sure every child learns to read, we can recommit to that bold vision for our children’s future.

In contrast, the high-stakes state assessments mandated by No Child Left Behind led to no improvement in reading and the same improvement in math skills as simply spending $1,000 more per student.