Debunking the Wealth Tax Discourse

What critics get wrong—and what they should be arguing about instead

Many people use the holidays as a time to unplug. Others dive deeper into the trenches, disregarding their inboxes but dedicating more time to the online discourse. If you’re in the former camp, congratulations! You’ve probably had meaningful time with your loved ones, but you’ve missed the heated debate surrounding California’s proposed ballot initiative on the 2026 Billionaire Tax Act.

This policy proposal would impose a one-time 5% tax on the total wealth of California’s billionaires (about 200 people) and is projected to raise about $100 billion, 90% of which would go toward state-funded healthcare services with the rest going toward food assistance and education programs.

As you would expect, people have had calm and measured reactions. Some like Larry Page and Peter Thiel are reportedly exploring leaving the state. Others have publicly voiced their vehement opposition:

David Sacks, Trump AI Czar: “After blindly funding the Left for years, Silicon Valley is finally realizing what time it is. Dinner time. And they’re on the menu.”

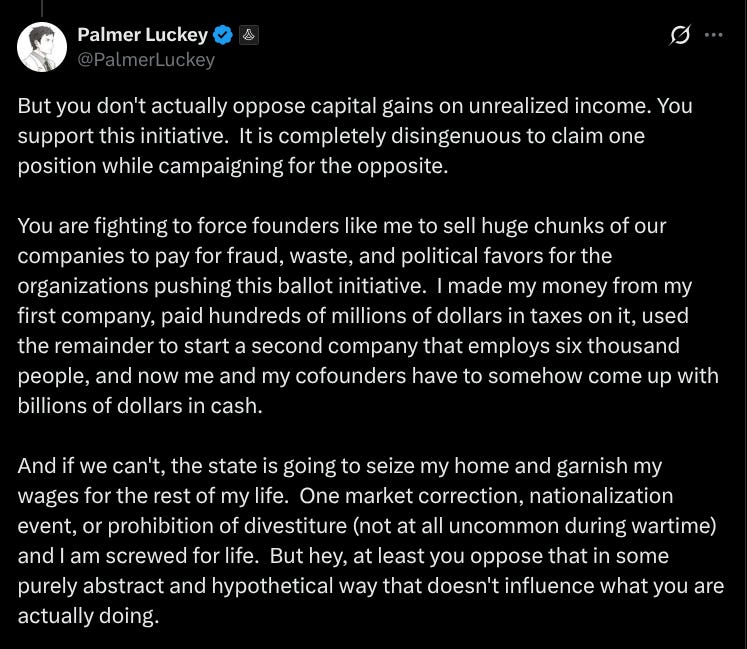

Palmer Luckey, CEO of Anduril: “You are fighting to force founders like me to sell huge chunks of our companies to pay for fraud, waste, and political favors for the organizations pushing this ballot initiative.”

Garry Tan, CEO of Y Combinator: “[T]his will kill little tech in California. Big tech founders will leave but also the next tech companies won’t start here at all.”

Alexis Ohanian, Founder of Reddit: “We’re absolutely going to have to figure out how our society adapts to a rapidly increasing wealth gap, it’ll be required to preserve our republic, but the answer is definitely not taxing unrealized gains.”

On the other side, Ro Khanna, the Congressman who represents Silicon Valley, has openly supported the proposal, redirecting FDR’s sarcastic line “I will miss them very much” to those threatening to leave California. Unsurprisingly, he’s facing mounting backlash from tech leaders, despite his best attempts at using X as a place to have a substantive policy discussion.

Without diving into the details of California’s nascent proposal, I wanted to write about some of the common critiques of wealth taxation. I spent nearly a year helping the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) Chief Economist think through some of the legal and economic questions around the Biden Administration’s proposed “Billionaire Minimum Tax,” which is effectively a tax on the unrealized capital gains of the uber wealthy. Given the country’s deteriorating fiscal situation, Democrats need to be serious about tax policies that raise revenues. Doing so demands weighing the substantive and political trade-offs for different proposals and deciding which proposals to prioritize. Smart people can and do disagree on whether we should tax wealth for many reasons. But, it’s crucial to recognize and rebut the unrigorous arguments the loudest voices often make that prevent serious deliberation.

Frequently Asked Questions

The questions that often drive public opinion and dominate debate around wealth taxation are often presented as complicated and determinative. In reality, they have pretty straightforward answers. Whether or not the algorithm brought the California wealth tax debate to your feed this week, you’ll likely see some of these arguments any time a wealth tax enters the political conversation.

Won’t founders have to sell their companies to comply? No. Every serious proposal addresses this valid concern. The Biden Administration’s proposal, for example, would allow founders with illiquid wealth to opt into deferring tax payment on illiquid assets and later paying a deferral charge upon the realization of their assets. In other words, they would only have to pay when they ultimately cash in and would have a small fee for the time value of money they enjoyed by deferring payment. In their proposal, Emmanuel Saez, Danny Yagan, and Gabriel Zucman propose offering entrepreneurs the ability to prepay their cash taxes using a no-risk government loan.

What happens if a taxpayer’s assets drop in value? Some argue that if the wealthy pay taxes on “paper money,” they could be left in a financially precarious position if the value of their assets fall. Again, serious proposals account for this very real possibility. For example, you might have paid the tax because you owned $100 million in a company but then that company goes bankrupt. In that case, if your net worth drops below the threshold for the tax (i.e., they’re not uber wealthy anymore) they could be refunded.

Won’t this discourage entrepreneurship? Gary Tan and others argue that wealth taxation would disincentivize entrepreneurs from founding companies. However, the tax only applies once a founder has a net worth exceeding a high threshold, be it $50 million, $100 million, or more. And, given the deferral mechanisms described above, a founder with most of their wealth tied up in their own company could defer the tax.

Won’t these gains already be taxed when they are realized? In theory, yes. In practice, no. That’s because the uber wealthy follow a strategy commonly referred to as “buy, borrow, die.” Essentially, the wealthy accumulate assets that rise in value, they borrow money from banks to live off the value of those assets instead of actually selling the assets and triggering capital gains taxes, and then, when they die, their heirs don’t have to pay taxes on the appreciation of those assets. And many of those assets aren’t hit by the estate tax either because the wealthy move assets out of their estates and into trusts. Rogé Karma wrote eloquently and in more detail about this in The Atlantic.

Can’t people just leave to avoid the tax? This is a legitimate concern for a state-level policy, which would make any state proposal, including California’s, hard to successfully implement. It’s not hard to move states. However, this is a less legitimate concern for a federal policy. That’s because, as Saez, Yagan, and Zucman describe, U.S. citizens are taxed on their worldwide income even if they live on a yacht on Lake Como. To try to escape taxation, the uber wealthy could renounce their citizenship, but doing so would trigger a tax on unrealized capital gains if their net worth is $2 million or more (which is far below the $50-$100 million thresholds of typical wealth tax proposals).

How to assess a wealth tax

Those frequently raised concerns distract from four harder, foundational questions that policymakers should consider.

What is the goal of a wealth tax? When deciding whether a wealth tax is a good idea or not, it’s crucial to be clear-eyed about what problem you’re trying to solve. Proponents often offer three overlapping justifications. First, we should decrease wealth inequality – moderately or drastically (e.g., “billionaires are a policy failure”) – because such inequality is bad for society and/or a healthy democracy. Second, we should curb dynastic wealth. Third, we should focus on the need to raise revenues from an undertaxed base whose wealth has soared in recent decades.

Does a wealth tax achieve that goal? Once you name your goal, you have to assess if the proposed policy achieves it. Let’s say your objective is to raise revenues without distorting economic growth. President Biden’s aforementioned proposal would raise an estimated $360 billion over 10 years from the wealthiest 0.01% of American households. You can argue over whether the implementation of a wealth tax would affect economic growth, either positively or negatively. If revenue and growth are your primary metrics of success, you should decide whether the wealth tax is better than alternative policy proposals.

Is a wealth tax constitutional? Some think yes, some think no, and some think it depends on the structure of the policy. (Some say maybe it’s not worth testing out with today’s Supreme Court.) Policymakers must consider the long-term resilience of a tax proposal, especially given that administrations often only have one chance at major tax reform given legislative constraints.

Does the public support a wealth tax? Another part of the political resilience of the proposal is judging whether it has popular support. There’s certainly a chunk of people who want a wealth tax—remember Elizabeth Warren’s army of supporters chanting “2 cents”? On the other hand, recent research from Zach Liscow suggests that the broad public – not just the Silicon Valley crowd – is opposed to taxation on unrealized capital gains, even if the policy is restricted to the uber wealthy.

You might be frustrated that I’m not just giving a yes or no answer on any of these questions! That’s to demonstrate that there are valid reasons for people to disagree on wealth taxation, either for substance or politics. (Remember there were big disagreements about a wealth tax in the 2020 Democratic primary?).

Separating signal from noise

Answering those four foundational questions requires making value judgments and being clear about what you actually support. Is the level of wealth inequality in America good and should tax policy try to address it? How can we raise trillions in revenues to address our deficit? It’s much easier to say what Alexis Ohanian did: We should do something, just not this thing. That’s why it’s convenient to reject a wealth tax on the basis of implementation questions, especially those that on the surface sound complex and intractable. In reality, many of those concerns are a paper tiger.

You can tell when someone is reaching for a reason to say no when they can’t justify why they oppose alternatives either. For example, Zach Liscow and Edward Fox have suggested an alternative: taxing the borrowing of the uber wealthy. Under this policy, those employing a “buy, borrow, die” strategy would pay a tax when they borrow millions of dollars secured by their unrealized capital gains—in essence, the tax code would treat that borrowing as income just as those people actually do. And when they ultimately sell their stocks, they can deduct this tax from their capital gains tax so they don’t get taxed on it twice.

This alternative idea could be supported by people who are in favor of raising taxes on the wealthy but fundamentally oppose any tax on unrealized capital gains. Indeed, Bill Ackman has spoken in support of taxation on such borrowing and Gary Tan shared a post advocating for the proposal. But for others who continue to reject any revenue raising idea, you may start to think they just oppose higher taxes in general but don’t want to say it.

Raising enough revenues to address our debt and invest in America will require making hard choices. As we deliberate those choices, it’s important to be honest about the legitimate reasons to support or oppose any policy and to be quick in pointing out bad faith arguments like many we’re seeing here.

P.S. Lastly, as many of us make the New Year’s resolution to go to the gym more, my friend Ben reminded me of something important: whether realized or unrealized, you won’t be taxed on those gains.